Seeing wildlife in real life is one of the most treasured memories we can have and yet, it is critical that we make sure to pick an ethical wildlife encounter.

Being a responsible traveller is important. Conservation of wildlife is a topic dear to my heart and I want to provide you with practical advice on how to make sure your next wildlife encounter is ethical.

In most countries we can find at least a couple of types of wildlife encounters, the most well known of them being a zoo or a safari game reserve.

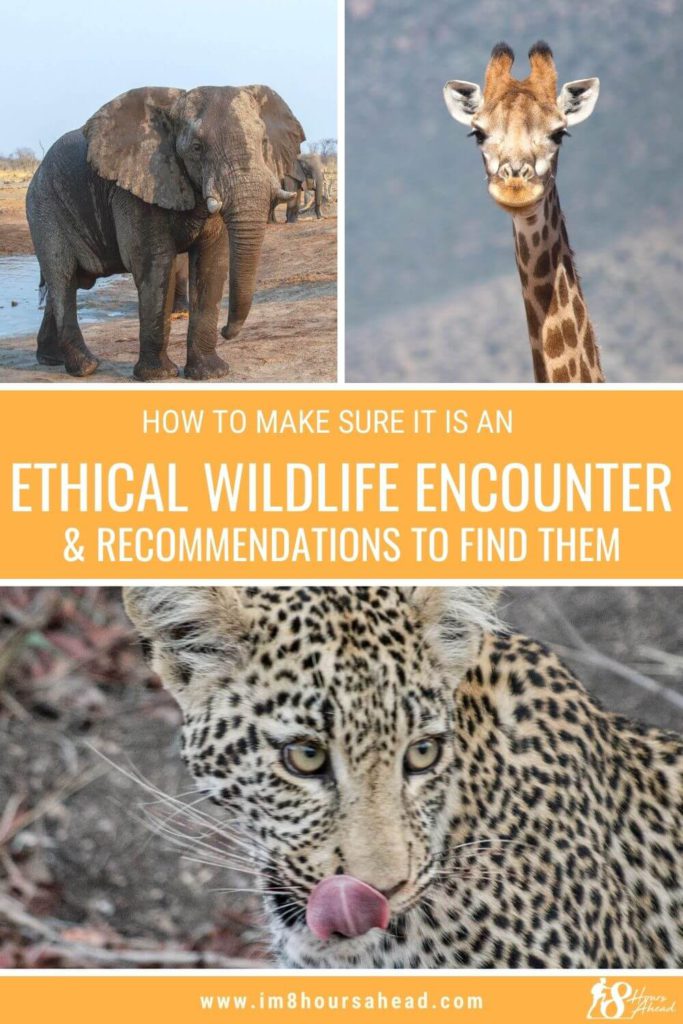

A once in a lifetime encounter with wild animals is on most of our bucket lists. Seeing a lion, elephant, gorilla or giraffe in Africa (to name just a few) in real life is an experience you will never forget. Seeing polar bears or whales is another popular one, though there are many examples from different parts of the world.

In some places, the wildlife is left in its natural habitat and humans visit in the hopes of catching a sighting of the animals. These animals roam freely and are (if anything) only accustomed to car or boat sounds.

In other places, the animals have been taken out of their natural habitat and now live in a different location. As a rule of thumb, if the animals are not in their natural habitat this is your first red flag.

Reasons for moving an animal out of their natural habitat can be many: to “educate” societies on animals from around the world (zoo’s), to show off (circus), to reproduce as the species is endangered, to rehabilitate (rehabilitation centres)…

In a time where wild animal populations are decreasing globally, picking your wildlife providers and activities carefully is more important than ever.

Table of Contents

So how do you know if your wildlife encounter is ethical?

There are a number of factors that can help you decide. Some of them are available publicly and pretty easily and some aren’t and you might need to dig a bit, send an email or phone someone.

First hand reviews from other travellers with details regarding how the animals live and are treated are a good starting point. These are easily found on review websites.

Now there can be many opinions on the topic, and mine leans towards: “If they are not in the wild you shouldn’t be visiting them.” But as there are exceptions for conservation/rehabilitation, it is important to digest all information prior to making the decision.

Some facts for further context and to help you understand this article better:

These pointers can be applied to game reserves, national parks, rehabilitation centres, sanctuaries or centres for endangered wildlife.

GFAS defines a sanctuary as “a facility that provides lifetime care for animals that have been abused, injured, abandoned, or otherwise in need”.

Unfortunately there are many animals who have lived all their lives in captivity and don’t know how to live or find food by themselves. These animals cannot be released back into the wild. They were part of a show, or were privately owned and are accustomed to humans and to being fed so they cannot be released.

Giving these animals the closest possible experience to what they’d have in the wild (big enough natural habitat, resembling the wild, minimal to no interaction to humans) is critical. For example, imagine a leopard who has lived half-drugged and chained up all his life in a centre where tourists could pet him.

He can never be released into the wild, but if he is moved to a facility that doesn’t chain him up or drug him, one that provides him with companions, in a wide enclosure, that resembles the bush – that is a positive outcome for him.

Each case has to be treated differently but by following these pointers you can have a pretty clear idea.

How to ensure your wildlife encounter is ethical

Breeding

Making sure the facility is not breeding their animals is one of the most important items on this list.

There are three options here:

- A breeding centre for critically endangered animals. As the name suggests these exist to create more members of the species and they will be breeding. In this case, making sure they are reintroduced into the wild and that their lives remain mostly unchanged is what concerns us.

If males and females live together in an environment that looks like their natural habitat, and once they get pregnant, facilitators make sure that the baby makes it through the first crucial months, this is good.

The idea is that these animals will be released back into the wild (especially the young). Some of these centres do have previously abused animals that cannot be released into the wild as they don’t know how to hunt (for example). If their lives remain untouched except for food being provided, that is a not terrible case of breeding. - The facility is not actively trying to get animals pregnant but females and males live together in enclosures. That they are not doing it actively doesn’t mean they are trying to stop it. Animals do naturally mate so offspring from those species should be expected, hence lengthening the business operations, as the animals never die.

- They are trying to avoid kids: that could be putting the animals on contraceptive pills for example to avoid babies. In this case once the current animals die, the business will perish. They are giving the current animals a chance for a happy life (even if that means seeing humans without touches) but they don’t want to prolong the life of animals outside of their natural habitat.

To breed, sell or trade animals is a no-no. Animals don’t leave the sanctuary except for emergencies or vet care.

Touch or walk

In the natural world you would not touch a wild animal. If you are going on safari you will watch the animals from a boat, a car or even walking – but you will never touch them. They are wild and you keep a respectful distance from them.

Going to a sanctuary that has lions or tigers (those are the most common animals, but it can be any animal) where you can touch them is a clear no. Those animals are either drugged so that you can touch them or are trained using pain in the case that they do not follow orders. This training generally happens with very young babies and are usually brutal, leaving animals scared and scarred for life.

You are not permitted to feed, cuddle, pet, or pose for photos with animals.

Walking next to predators or elephants is also a sign of the sanctuary not being ethical. It is not a natural behaviour you would see in the wild.

Chains

Animals that are chained do not have the mobility they need. Chained animals are kept at a certain distance mostly from approaching humans so that humans can’t be harmed. This practice harms the animal’s mobility as well as their physical body and can be very painful.

Accreditation

The sanctuary or reserve is accredited by a reputable organisation. Some of them are:

- Global federation of animal sanctuaries (GFAS)

- American Sanctuary Association (ASA) in the USA

- Wildlife Conservation Fund in South Africa

- World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF)

- Project Aware

- Panthera

Performance

Animals do not perform.

This includes a circus performance but also zoos and museums that aim to teach young kids about different animals. The animals aren’t used for commercial purposes like adverts or movie recordings.

Animals aren’t ridden either, as for you to be able to ride an elephant they are trained using painful techniques from very young to accept human riders, and if they misbehave they get even more pain (as tourists are in the vicinity or on top of the animal).

Enclosures or lack of thereof

The best indicator to know whether a wildlife encounter is ethical or not is that animals are not fenced off.

For example Kruger National Park has thousands of sq meters and there are only fences on the outskirts to ensure that local communities and animals don’t have an issue over space. In Bwindi forest in Uganda, gorillas aren’t fenced at all and can get out of the forest if they want to.

If the animals are enclosed, the enclosures are REALLY big and replicate (or are) a natural habitat. This is to ensure the environment is good for the animals and has enough space as well as entertainment (trees, rocks, rivers…).

Type of registration

The sanctuary is registered as a non profit and/or has worked with other wildlife or animal conservation non profits.

Guests are educated on wildlife needs, behaviour and injustices. The message is educational on premises, in order to spread the word that protecting wild populations and stopping the wildlife trade and poaching are important.

Educating the general public on the realities of the animal trade and poaching is the best thing an organisation can do – together by showing the right way to visit animals. By doing this people who were not experts prior to their first visit leave the sanctuary/reserve with knowledge they can act on or tell their circle about etc and that creates more people that know about the topic.

How to choose your ethical animal encounter? Here are some wildlife encounters you can do right now

Ok Anna, I’ve read it and I get it! Can you give me some options of ethical wildlife encounters right now? Can I do car game drives or walking safaris? Is that a good option?

YES!

These are places I have personally visited or know about through 3+ years of event and trip organization in Africa and they are reputable, but there are also many others!

- Bwindi National Park, Uganda – Gorilla trekking

- Volcanoes national park, Rwanda – gorilla trekking

- Kruger national park, South Africa & Greater Kruger National park reserves including: Sabi Sands, Timbavati, Klaserie, Manyeleti, Thornybush

- Masaai Mara Game reserve, Kenya

- Serengeti Game Reserve, Tanzania

- Hwange game reserve, Zimbabwe

- Okavango Delta, Botswana

- Samara Private Game Reserve, South Africa

There are many game reserves in Africa that offer safaris without changing the animal’s lifestyle. Those are just some of the most well-known or famous ones in southern and east Africa.

As always, do your own research before travelling to make sure your wildlife encounter is ethical!

Use this article as a guide and PIN IT FOR LATER!